James Fogarty’s first Purple Heart came in an incident when his point man Bobby G. Swanson caught a Viet Cong bullet and later bled to death.

James Fogarty’s first Purple Heart came in an incident when his point man Bobby G. Swanson caught a Viet Cong bullet and later bled to death.

Mr. Fogarty was grazed across the forehead and received a facial wound. In his year of leading sweeps and ambushes across the Vietnam countryside, this was his only casualty. And to this day he still holds himself responsible.

This sense of honor and personal responsibility should come as no surprise.

Mr. Fogarty’s father was a Naval Officer during World War II and encouraged him to consider a career as a military officer.

In his last two years at the University of Scranton, Mr. Fogarty completed Army ROTC training, and upon graduating signed on for a five-year contract with the Army.

Had he not enlisted, he certainly would have been drafted. In October 1968, with the war heating up, he received his orders for Fort Benning Infantry School.

“Twenty eight of us were commissioned as Army Second Lieutenants and were assigned to the infantry,” Mr. Fogarty said.

It was a 12 month cram course at ROTC Officers Training School with much of the training done by ex-Vietnam infantry sergeants. It was Jungle Warfare School and Heavy Mortars School and Jump School, in which Mr. Fogarty practiced parachuting out of C-130s.

In addition to map reading (“The only map I knew how to read was a subway map,” Mr. Fogarty said), he learned battlefield tactics, a kill or be killed readiness, and most importantly, he was taught to lead.

The war was eating up Second Lieutenants. Troops right out of high school needed leadership on the battlefield. At 23, Mr. Fogarty found himself in a steamy Asian warzone commanding a platoon of teenagers.

As Mr. Fogarty says, “In Vietnam the life expectancy of a Rifle Platoon Leader was 27 minutes to two weeks.”

As Mr. Fogarty says, “In Vietnam the life expectancy of a Rifle Platoon Leader was 27 minutes to two weeks.”

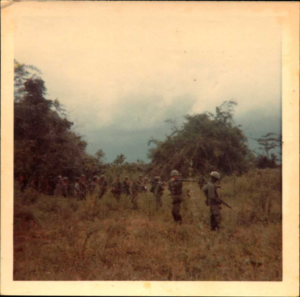

He was under constant pressure. The twenty-five men under him depended on his vigilance. He had to know their position at all times and if everyone was accounted for. He had to make sure they were all carrying proper weaponry, grenades, extra ammo, and a machete for hacking through the jungle.

He had to keep them off trails and out of tunnels. He had to keep them clean and make sure they washed. There were no sick days for rashes or infections.

At the slightest noise or provocation, he had to get everybody down and out of harm’s way, then ascertain the threat.

“The key to survival was the men first and the mission second,“ Mr.Fogarty said. “I adapted missions to make sure my men were protected. This was my justification to insure that we all got home alive. This is the time I started to really understand fear.”

“Early missions were from our Fire Support Base and onto Navy riverboats to sweep the area along the river,” Mr. Fogarty said.

Once they were taking small arms fire from a hedgerow of trees. Mr. Fogarty checked his map and realized the trees were only 50 feet deep & behind them was a large open field. He had his men outflank the Viet Cong and forced five of them back out into the field. They disappeared into a sea of five foot high elephant grass. He called in a napalm strike.

“Within five minutes the field was smoking and barren except for some areas that continued to burn,” Mr. Fogarty said. “These areas looked like trees burning until we realized that they were the bodies of the Viet Cong. This event redefined my mission.”

The tactics were brutal but necessary. Not one man in the platoon was lost. Mr. Fogarty had solved the problem of insurgents and successfully protected his men.

And he proved he could read a map. “I was very well trained,” Mr. Fogarty said. “I had wonderful commanders. I was with an infantry division that knew what they were doing, the 25th Infantry, the famous Tropic Lightening, 4th Brigade of the 9th Infantry, the Manchus. They are very well respected, even when you read about them now.”

And he proved he could read a map. “I was very well trained,” Mr. Fogarty said. “I had wonderful commanders. I was with an infantry division that knew what they were doing, the 25th Infantry, the famous Tropic Lightening, 4th Brigade of the 9th Infantry, the Manchus. They are very well respected, even when you read about them now.”

They mostly stayed at Chu Chi, one of the Fire Support Bases, in the south, in the Mekong Delta, but sometimes they would do insertions into Cambodia and run missions. There were never civilians around. To Mr. Fogarty, the Cambodian landscape untouched by war seemed idyllic and dreamlike.

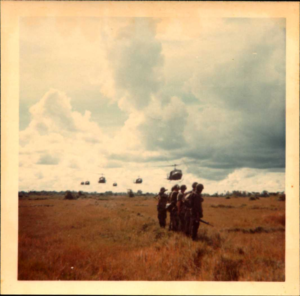

“We began to work at night and sleep during the day at the support base. We were being taken to where the enemy was by helicopter.” Mr. Fogarty said. “When we weren’t getting enough body count, the missions became more challenging, more risky.”

Mr. Fogarty would stage ambushes with 3 squads at night on trail junctions several hundred yards from each other. The kill zones could not face each other & the artillery grids had to be plotted carefully.

Then Mr. Fogarty had to make sure the squad leaders were coordinated so all the teams would operate seamlessly in the dark.

One ambush was set off “when one guy thought he saw movement” and opened up on the mirage. The troops were eager to inspect the kill. Mr. Fogarty had all he could do to make them wait until morning.

At first light, they found one lone Viet Cong corpse with his tattered cap beside him on the ground and a picture of his family inside the cap.

These night missions continued and “for months we never found anything.” Night after night, anxiety and dread, with no adrenaline rush of combat. A recipe for long lasting traumatic stress.

After six months leading a standard rifle platoon, Mr. Fogarty thought he caught a break. He was assigned to the recon group of the First Brigade 25th Infantry. It relieved him from being a Platoon Leader.

Their mission was to develop target situations for other platoons and companies to respond to. They buried sensors to detect Viet Cong foot traffic.

It was on such a mission that Bobby G. Swanson was fatally wounded. A Duffle Bag Alert Device was seeing a lot of activity, ”almost as if someone had been camping on it,” Mr. Fogarty said, and they were sent out to check on it.

They landed and their Vietnamese scout Neu heard talking from Viet Cong hiding in a hole. Their platoon Sergeant was on R & R, so it was up to Mr.Fogarty to instruct Neu to tell them to surrender.

“He called out in Vietnamese,” Mr. Fogarty said, “And they opened fire on us. Bobby turned and was shot in the buttock, Neu was shot in the foot, and I was grazed in the face. My radio man fell to the ground and pulled the wire out of the handset while I was still holding it.”

Now they had no radio and were cut off from contact with the chopper. They also had no medic. They never had a medic. Mr. Fogarty crept forward and dragged Bobby back to safety.

“We carried Bobby 50 yards to the landing zone. I told the two rifle men to strip off his clothes. I popped purple smoke to signal the helicopter. We stood on the LZ holding him up naked.”

He sent Bobby on the scout chopper back to the support base. When Mr. Fogarty arrived there, he discovered Bobby had bled to death. He was emotionally wrung out. Guilt haunted him.

He was debriefed and “there were more questions than usual” from intelligence. His men were also interrogated. But the fact remained– there was no medic, and no NCO. “And weeks later I got a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star for Valor,’ Mr. Fogarty said. “We continued our challenging missions with lots of time off.”

He was debriefed and “there were more questions than usual” from intelligence. His men were also interrogated. But the fact remained– there was no medic, and no NCO. “And weeks later I got a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star for Valor,’ Mr. Fogarty said. “We continued our challenging missions with lots of time off.”

Each night Ta Ning was either mortared or rocketed. Mr.Fogarty earned his second Purple Heart when his barracks was hit by a mortar.

“Suddenly we heard a crash as the round came through the roof and flattened the barracks. Shrapnel tore through my underarm.”

Without Mr.Fogarty knowing, each time he was wounded the Red Cross delivered a telegram to his parents, telling them the news.

The arm was not healing due to the heat, so he was shipped home a month early.

He came through the airport in Oakland and there were people screaming at him. He was in uniform, wearing his jump boots and medals, his arm in a sling, and several loudly shouting the epithet “baby killer’ at him. One actually spit at him. “I never put my uniform on again,” said Mr. Fogarty.

“A civilian came up to me and took my arm, a businessman. He said, ‘Lieutenant, the war is very unpopular. Come with me and I’ll show you where your gate is’,” Mr.Fogarty said.

And that was his reception home. This was a guy who put his life on the line and was decorated for valor with two Bronze Stars for Valor, two Air Medals, two Purple Hearts, and New York State’s highest award: The Conspicuous Service Cross with four Silver Clusters. He is most proud of this last award because it represents the ideal of a citizen army.

Many of the quotes attributed to Mr. Fogarty in this article are in fact from a Vietnam memoir he wrote ten years ago. He was experiencing vivid dreams and memories, and the memoir was suggested as therapy, a chance to reconnect with the trauma of the battlefield. At times he is reminiscent of Tim O’Brien’s eloquent depictions of war in books such as The Things They Carried and If I Die in a Combat Zone.

Mr. Fogarty credits his therapist Larry Keating with helping the healing process and easing his nightmares. Mr. Keating is a licensed clinical social worker and the owner of Transitions Counseling Service in Smithtown, a private practice that assists those in need of social services, including veterans. The VFW in Westhampton also provides comprehensive support for active duty service professionals and veterans.

Mr. Fogarty credits his therapist Larry Keating with helping the healing process and easing his nightmares. Mr. Keating is a licensed clinical social worker and the owner of Transitions Counseling Service in Smithtown, a private practice that assists those in need of social services, including veterans. The VFW in Westhampton also provides comprehensive support for active duty service professionals and veterans.

In an effort to give Vietnam veterans their long-due recognition, Mr. Fogarty also spearheaded the VFW’s effort to build a Vietnam Memorial at the Westhampton Cemetery. Mr.Fogarty was charged with making contact with local veterans interested in having their names included on the memorial. He was wildly successful.

The rose-colored granite memorial, featuring the names of over 125 Vietnam veterans, was unveiled on Memorial Day, May 29, 2006.

Almost fifty years after Bobby G. Swanson’s death, Mr.Fogarty is making plans to visit his sister and perform a Memorial service at his grave in Texas. And if you drive out to the cemetery in Westhampton to see the Vietnam Memorial, there in the middle ranks you’ll find the name—Bobby G. Swanson.