When Dominic Lodato first served on the bench, he was assigned the David Berkowitz, AKA Son of Sam, case. Berkowitz told his lawyer he was going to put a curse on him. Judge Lodato was presiding over the civil case in which the victims were suing Berkowitz. “He was one nasty fellow,” Judge Lodato said.

When Dominic Lodato first served on the bench, he was assigned the David Berkowitz, AKA Son of Sam, case. Berkowitz told his lawyer he was going to put a curse on him. Judge Lodato was presiding over the civil case in which the victims were suing Berkowitz. “He was one nasty fellow,” Judge Lodato said.

This was not the first time in his long rich life that Judge Lodato confronted evil. His generation was called to fight the Second World War and he joined in this effort.

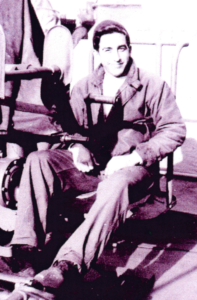

Judge Lodato’s father had served in the Navy in World War I. So following in his father’s footsteps, Judge Lodato enlisted in the Navy as soon as he graduated from Boy’s High School in Brooklyn in 1943. He was only 17. He had to get his parents’ permission.

He was sent to Newport, Rhode Island, for basic training. After basic, most of his classmates shipped out on the aircraft carrier WASP, but Judge Lodato was accepted into Quartermaster School at the Newport Naval Base, where he studied navigation, signaling and map reading.

The PT boats going past the base appealed to him, so he volunteered for serving with the Motor Torpedo Boats and made it into the program. “After training, I was assigned to Squadron 34 and they shipped me overseas to pick up the Squadron in England,” Judge Lodato recounted.

He spent nine days on a large troop ship zigzagging across the ocean for fear of U-Boat attacks. He was one of a handful of sailors among 4000 soldiers. In rough weather and choppy seas, the soldiers would get sick, but “the sailors knew what to do in bad weather,” Judge Lodato said. A group of destroyers would form a ring around the troop ships, creating a line of defense against any German U-boats in the area.

Judge Lodato was assigned to PT Boat 507, part of Squadron 34, which consisted of twelve PT boats. “We would go out, six at a time, on patrols only at night as it was too risky for PTs to be on patrols during daylight,” Judge Lodato said. “We patrolled the Normandy beachhead in France going all the way from La Havre down to the Channel Islands.”

Judge Lodato arrived in Normandy after D-Day in July 1944. The area was still buzzing with activity, with freighters and troop ships constantly arriving at the beachhead. The job of the PT boats was to keep the German E-boats away from those ships and keep the port open. The Squadron was constantly chasing off E-boats who would then be pursued by U.S. destroyers.

Equipped with three Packard marine engines, each running at over 1500 horsepower, the PT boats were faster than anyone on the water. “The British boats couldn’t handle the German E boats,” Judge Lodato said. “Our skipper Lt. Buel Taylor Hemingway was probably the best in the Squadron at handling our PT boat. We were probably the fastest boat. We felt very safe with him while on patrol.”

As quartermaster, Judge Lodato was third in command, but because of the stability of Hemingway, he never was at the wheel while on patrol.

“The Germans would engage us, harass us,” Judge Lodato said. There were flyovers by a plane they christened Captain Midnight who was up there taking photographs, doing recon. Another was called Washing Machine Charlie, probably for a distinctive engine. The first time it happened they opened fire at Captain Midnight, but were told, “Don’t waste your fire. You can’t hit them.”

“The Germans were very smart,“ Judge Lodato said. “The shore batteries would fire at us, but they tried not to hit us. PT boats have a big wake and they would fire at the wake.”

Hemingway’s reasoning was that if any PT boat was hit, the Air Force would go in and bomb them. “The Germans were pretty safe on the Channel Islands, so they didn’t want to make waves,” Judge Lodato reflected.

It was a dicey business. One time the radar station saw something too big for them on its screen. They were told not to engage. Hemingway and the crew never picked up the target, a mystery floating by, on or under the waves. “We had four depth charges but never used them. Four depth charges were not sufficient to take on a sub,” Judge Lodato said.

One time they made contact with a German ship but the weather was so bad, they couldn’t fire a torpedo and had to let it go. “It is very hard to fire a torpedo in that kind of weather,“ said Judge Lodato. “Our torpedoes were not very accurate.”

The torpedoes were a piece of work. The crew more or less had to roll the torpedoes off a rack, while dodging the spinning propellers & hope they went in the right direction. The torpedo would sink & then re-surface, “and then it would have to go 300 yards to arm itself.” If they didn’t have enough distance, the crucial 300 yards, the torpedo wouldn’t explode.

“We only had ten boats left out of the twelve after Normandy,” Judge Lodato said. “PT Boat 509 was sunk after a battle with a German gun ship. All hands were lost but for the radioman who was wounded and captured by the Germans.”

“After the Army had really gone through the countryside in France and Germany,” Judge Lodato explained that they set sail and left France in December 1944. The Motor Torpedo Boat fleet was on the way to Scotland where they would turn the boats over to Russia. Judge Lodato was handling the charts and told the skipper they were heading in the wrong direction. “We’re heading for Ireland!” he said. They were getting hit by wakes coming at them from boats in front. The lead boat was off course and taking the Squadron to Ireland. Judge Lodato corrected the situation, adjusting the co-ordinates and plotted a new course, saving the day for Squadron 34. He was 19 years old.

“On our trip to Scotland, our starboard engine separated from its moorings. I charted Wales as our safest port to enter and seek repairs,” Judge Lodato said. “At first we were refused entry but an English skipper who was going to enter the harbor told our skipper to follow him close off his stern and he will get us through the anti-submarine nets across the harbor.”

After repairing the engine in Wales, they made their way to Scotland and got the boats ready to turn over to the Russians. The Russian men were fighting on the front, so Russian women manned the freighters and loaded the PT-boats. Hemingway advised the Russian officers and taught them the intricacies of the boats. “Ours was one of the last PT boats to be put on the Russian freighter,” Judge Lodato said.

Motor Torpedo Boat 507 was headed for the Russian seaport of Murmansk, and that was the last Judge Lodato ever saw of it.

When the Germans surrendered, Judge Lodato was sent back to the base in Melville. He was then shipped to Charleston, Mass. where he trained Merchant Marine seamen to read charts and identify the locations of minefields. He never used his navigational and map reading skills again. Instead of boating, he took up golf.

After the war, he came home and furthered his education. He went first to Siena College in upstate New York and graduated in 1950 with a B.A. degree in sociology, a pre-law degree.

He graduated from Brooklyn Law School in 1953, and set out to practice law. He was a trial lawyer for nineteen years. He specialized in cases involving personal injury, real estate, and contracts, and represented some of the big insurance companies. For twelve years, he was a partner in the firm of Hauptman, Mangano and Lodato.

He went on the bench in 1975, appointed to the Criminal Court as a judge by Mayor Abe Beame. “I was nominated and ran for the Supreme Court in 1977,” Judge Lodato said. “I was elected and sworn in January 1978, for a fourteen year term.”

Judge Lodato served as a no-nonsense, tough judge for fourteen years. In the Son of Sam civil case, he took away Berkowitz’s social security benefits, refused to let him change his name and denied him the right to come to the courthouse. That earned the Judge the curse of Berkowitz.

He handled the case of the infamous Long Island garbage barge, a barge loaded with paper and debris that was turned away from every port. It journeyed 6,000 miles along the eastern seaboard and around the Gulf Of Mexico before returning to New York. “It came back to New York and was anchored off the Verrazano Bridge,“ Judge Lodato said. “Word came down from Governor Cuomo. Get rid of it. We don’t care how you do it. But get rid of it.” So Judge Lodato ordered the Brooklyn Borough President to stand down and the contents of the barge were incinerated in Brooklyn. The ashes were finally laid to rest in the Islip Town landfill.

Judge Lodato also served on the board of the Lutheran Medical Center in Brooklyn. Around 1990, he was asked to develop and run a Legal Affairs group. “When I put the whole department together,“ Judge Lodato said, “I was saving Lutheran Medical over two million a year.”

In 1999, after the president resigned, he served as interim president for six months. That stretched into three years. Judge Lodato finally resigned in 2002.

In the last few years he’s been a Trustee administering a ninety million dollar trust formed for payment of outstanding malpractice law suits against LI College Hospital in Brooklyn. “We started with over 200 cases and we are now down to about 60,” Judge Lodato said. He is still doing that today.

In his spare time, Judge Lodato likes to read the paper and go on trips through the Hampton Bays Library.